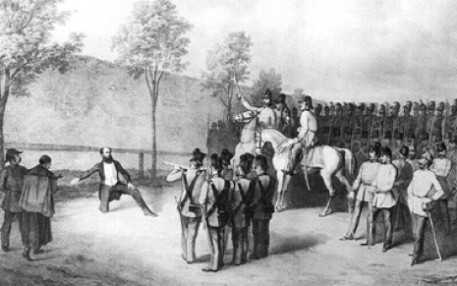

The Execution of Lajos Batthyány and the Martyrs of Arad – 6th October 1849

Szöveg: hungariandefence.com | 2011. október 6. 6:43Lajos Batthyány, the Prime Minister of the first responsible Hungarian government and the 13 martyrs of Arad were executed 162 years ago, on 6th October 1849. We commemorate the historic event by excerpting from the book “For the Homeland Unto Death – 1100 Years” published by Zrínyi Média, which is available in our Digital Library.

was followed by military invasion

and bloody reprisals. The judgement

of the Emperor and his government was implemented

by Field Marshal Haynau, who

bragged, “I will hang the rebel leaders," “I will

have the turncoat officers shot," “I will pull up

the weeds by their roots, I will set an example

to all of Europe as to how rebels are to be dealt

with and how to ensure order, calm and peace

for a century."

The executions followed one after

another throughout the dark autumn of 1849.

On 6 October, the Prime Minister of the first

Hungarian government, Count Lajos Batthyány,

was shot in Pest, and the same day twelve heroic

generals and a colonel were executed in Arad.

The names of Lajos Aulich, János Damjanich,

Arisztid Dessewffy, Ernő Kiss, Károly Knézich,

György Lahner, Vilmos Lázár, Károly Leiningen-

Westerburg, József Nagysándor, Ernő Pöltenberg,

József Schweidel, Ignác Török and Károly

Vécsey stand as a memorial and a sign that Hungarians,

Germans and Serbs fought and died side

by side, for liberty!

After the executions, retribution continued

with fearsome sentences by the thousand: captivity

in heavy irons, damp dungeons and hard

labour, confiscation of property and punitive

military service. The blind thirst for retribution

exceeded the limit of any inclination to make

peace. If the war made heroes, the reprisals made

martyrs, and the nation should never forget them.

was again detached, new crown provinces

were set up under the names of Serbian Voivodina

and Temes Banat; the remainder of the country

was divided into five districts administered first

by soldiers and later by district bailiffs, beneath

them “county prefects". The Emperor’s uncle,

Archduke Albrecht, was appointed at the head

of the occupied and annexed country. The real

power was held by the Minister of the Interior

in Vienna, Alexander Bach. An army of his administrators,

the “Bach Hussars" flooded the

country.

Hungary in defeat was “pacified" by military

occupation and total absorption – political,

administrative and economic – into the

Habsburg Empire. This was designed as a punishment

for the country having abused its

constitutional rights by “rebellion". Hungary

was not alone in being dealt with in this way;

all the peoples of the Empire were treated similarly.

The bitter spirit of the age was that

nationalities loyal to the dynasty received in

reward the same as the Hungarians did in punishment:

raw tyranny and injustice. The only

one of the 1848 reforms recognised under

absolutism was the freeing of the villein peasants;

equality under the law, and all other right and

institution of constitutionality and liberty, were

repealed. The national autonomy promised in

the 1849 Olomouc Constitution was left to rest

on paper. In fact the constitution itself was soon

dropped, and on the last day of 1851, unlimited

imperial absolutism was proclaimed.