The Battle of Nicopolis – 28 September 1396

Szöveg: hungariandefence.com | 2011. szeptember 28. 6:01The crucial battle of Nicopolis was fought between the Ottoman Turks and the Crusaders’ army 615 years ago, on 28th September 1396. We commemorate the historic event by excerpting from the book “For the Homeland Unto Death – 1100 Years” published by Zrínyi Média, which is available in our Digital Library.

After the death of Louis the Great without

a male heir, the throne passed to Mary.

The Queen Mother and the Horváti family,

who wielded considerable power in the south,

each supported a different claimant, but it was

ultimately Mary’s betrothed, subsequently her

husband, Sigismund of Luxemburg, who was

crowned king. This of course did not mean

he acquired supremacy over the kingdom.

To consolidate his position, he took on as

allies the Garai–Cilli–Stibor league of barons,

against other such leagues, but during his

reign he relied on the Rozgonyi–Pálóczi–

Hédervári families.

over the barons was the weakening of the

system of royal castle estates, and thus the

weakening of the country’s military potential.

He had to take account of the rising military

strength of Poland, Bohemia and Venice. The

greatest threat came from the Turkish Empire,

which endangered the very existence of the

kingdom, and not just the southern counties.

In 1397, the Diet created the institution of

telekkatonaság (militia portalis). This required

the equipping of 5 mounted archers for

every 100 tenant peasant plots in a defensive

war. This, however, meant that the soldiers

were effectively peasants, and were difficult

to mobilise. The barons were increasingly

less willing to participate in defence of the

country’s borders. The 1439 Diet decided that

mercenaries should be employed for border

defence. The institution of military barons

was designed to create independence from

the leagues of barons. In exchange for part of

the royal revenues, they were obliged to raise

heavy cavalry.

The measures taken in defence of the country

indicate Sigismund’s mastery of kingship. He

is also associated with a major diplomatic

accomplishment in being the organiser of the

last European crusade.

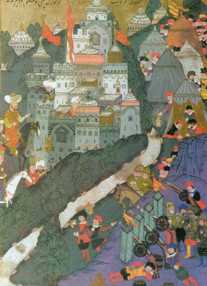

In 1394, Sultan Bayezid ejected Prince Mircea

of Wallachia and installed the puppet Vlad in

his place. Mircea fled to Hungary and asked

Sigismund’s help. The next year, Sigismund

personally led a campaign to Wallachia, defeated

the Turkish-leaning voivode and helped Mircea

the Elder to regain his throne. The Hungarian

armies reached the Danube and recaptured Little

Nicopolis from the Turks. The military position

now made it possible to force the Ottomans back,

but the Kingdom of Hungary did not have the

military strength to do so on its own, and he called

upon the support of cavalry from throughout

Europe. Sigismund approached the European

powers via the talented diplomat Miklós of

Kanizsa, who found the most receptive ears in

France. A contingent of nearly 1000 armoured

knights set off for Hungary under the command

of Count John of Nevers, heir to the throne of

Burgundy.

In summer 1396, the German Knights and

knights of the Johannites, as well as knights from

England, Poland, Styria, Germany and Bohemia

were assembled in the royal camp and waiting to

set off on what they were confident would be a

successful campaign. “If the sky should fall, we

will hold it up with the tip of our lances!" was

the knights’ watchword. The Crusaders set off

on their campaign in two columns. One column

united with the Transylvania army in the Olt

valley, and the other, led by the King, marched

beside the Danube to Nicopolis, one of the

main bridgeheads for Ottoman armies into the

Balkans.

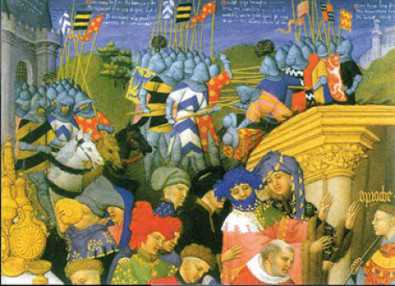

and a large number of soldiers. Without suitable

siege engines, the Christian army attempted to

starve the defenders out. The relief army led

by Sultan Bayezid approached the town on 24

September. A council of war sat in the evening

to draw up a plan of attack for the next day.

Sigismund and his commanders were familiar

with the Ottoman tactics of initially deploying the

light cavalry, who then retreated to the solid body

of the well dug-in infantry. This had the function

of breaking the momentum of the enemy charge

and preparing the way for the counter-attack

by the heavier cavalry. This was the basis of

the Hungarians’ proposed order of battle. The

Hungarian cavalry would have started the attack,

preparing the field for a charge by the allied heavy

cavalry. The French demurred, insisting that

they attack in the front rank, and that the other

groupings take part only in the development of

the charge. Despite Sigismund’s every effort, no

consensus could be reached. On the morning

of 25 September, the Hungarian King went in

person into the French camp and attempted

to persuade the commanders to change their

view, again without success. He also perceived

that the French contingent had effectively

decided to operate on its own. They prepared

for battle without heed for the other forces. The

subsequent course of events suggests they must

have had their own plan of attack, based on false

knowledge they had acquired about the Turks.

They planned to break up the Ottoman cavalry

in a sweeping charge, dismount, and engage the

infantry on foot. The problem was not so much

with the French commanders’ excessive selfconfidence

so much as their failure to conduct

the battle together with their allies. They were

trained fighters, with excellent weaponry and

armour, but their inability to cooperate with allies

in battle had been proved by the 1346 Battle of

Crécy, where the French knights ran down their

own Genovese crossbowmen during the charge.

It was to be feared that the Hungarian and

Wallachian cavalry fighting in the van at Nicopolis

would be in for a similar fate, because in the

heat of the battle, it would have been difficult

for the French to distinguish foreign-speaking

soldiers from the Turks. Upon returning to

camp, the King immediately issued the order to

take up battle order. In the meantime, the French

moved out of their camp in long rows, taking

up a formation in the field in front along a long

line. As soon as they had formed up, they started

advancing against the Turkish cavalry which had

just appeared at the edge of the field in front of

them.

The Hungarian and allied troops were not

yet ready to charge. István Laczkfy commanded

the right wing, King Sigismund and Herman of

Cilli the centre, and Voivode Mircse of Wallachia

the left wing. The right wing consisted purely

of Hungarians, the centre of Hungarians and

Germans (mainly Bavarians and Styrians), the

former commanded by Count Herman of Cilli,

the latter by the Kanizsais – János, Rozgonyi

and Forgách Maróthi. The left wing contained

purely Wallachians. Behind them was a reserve

of Bohemians, Poles, Serbs and Bosnians led

by Miklós Garai, Ban of Croatia. The closed

charge of the French swept away the Turkish

light cavalry standing in the front. Pursuing the

fugitives, they reached the camp of the Ottoman

infantry, surrounded by an obstacle of pointed

stakes driven into the ground at an angle.

French dismounted, arranged themselves into a

tight mass, and started to charge. The Janissaries’

arrows must have made little impression on their

armour, and they pressed forward unhindered.

The Turkish infantry soon started to retreat.

Until that moment, the hope of victory was on

the Christian side. But the dismounted knights

were not capable of pursuing the retreating

Turks. They would have needed the Hungarian

and allied forces that had been left behind.

The

Sultan now deployed the Spahis, who attacked

the French knights’ horses. The shield-bearers

fled towards the camp, as did the horses. In

the meantime, the King gave the command to

advance, but they had not reached the Janissaries’

positions when the mass of riderless French

horses, with the Ottoman cavalry behind, rushed

towards them. This slowed down the advance and

disrupted the battle order. Through determined

struggle, however, the Ottoman cavalry was

pushed back and the troops led by the King

reached the remnants of the French knights

fighting on foot. A bloody hand-to-hand combat

ensued between the cavalry, in which Sigismund’s

army began to make headway. The battleground,

however, harboured an unpleasant surprise. A

substantial troop of Serbs was hidden in one of

the alluvial valleys, and made a surprise attack on

the flank of the Christian army. The momentary

confusion allowed the remnants of the Ottoman

army to regroup and launch a counter-attack.

Control slipped from Sigismund’s hands, and

his multinational army took flight in whatever

direction they could.

The defeat was definite proof that the main

task of the following decades would be to halt

the Ottoman expansion. The failure of the

campaign pointed up the importance of strong

defence, which Sigismund sought to provide by

a set of buffer states along the southern borders,

and when this failed, a line of defensive forts.

Around 1435, he directed every available source

of revenue in the south of the country towards

defence of the threatened border, and put the

entire line of border fortresses between Szörény

and the Adriatic under centralised command.

in 1410. It was then he called the Council of

Constance (1414–1418), to which he succeeded

in bringing all of Europe to the negotiating table.

The Council’s main task was to address the church

schism which had been threatening since 1378.

There were three popes at the time, all of which

had a country which swore allegiance to him

alone. Sigismund succeeded in making all three

popes resign, and to have one, Martin V, elected

in their place. The second issue was church

reform, because the authority of the church at

that period had fallen to an all-time low. After the

election of Pope, however, the reforms came off

the agenda. The Council of Constance examined

the Czech reformer John Huss, who Sigismund

at first supported, but under pressure from the

bishops, condemned to death.

In 1419, after

the death of his brother Wenceslas, Sigismund

put forward his rightful claim to the throne of

Bohemia. His actions in Constance, however,

had set him against the Czechs, and the 17-year

Hussite Wars began, against which a crusade was

proclaimed. In 1431, he succeeded in dividing

the rebels. The Calixtines changed to his side,

and with their help, he struck the decisive blow

against the Taborites in 1434. It was towards

the end of the Hussite Wars that he scored his

greatest success: in 1433 the Pope appointed him

Holy Roman Emperor.

The Sigismund Era was

a turning point in Hungarian military affairs. The

burgeoning Ottoman Empire not only threatened

the southern border lands, it directly endangered

the kingdom itself, and in subsequent decades,

defence against Turkish conquest became the

prime task of the Hungarian military.